Dec 17, 2025

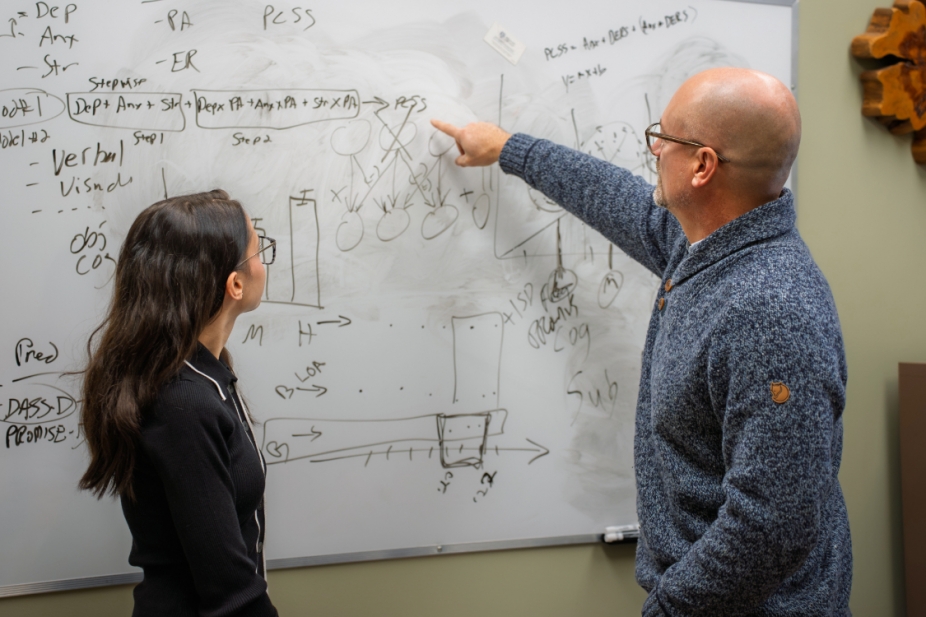

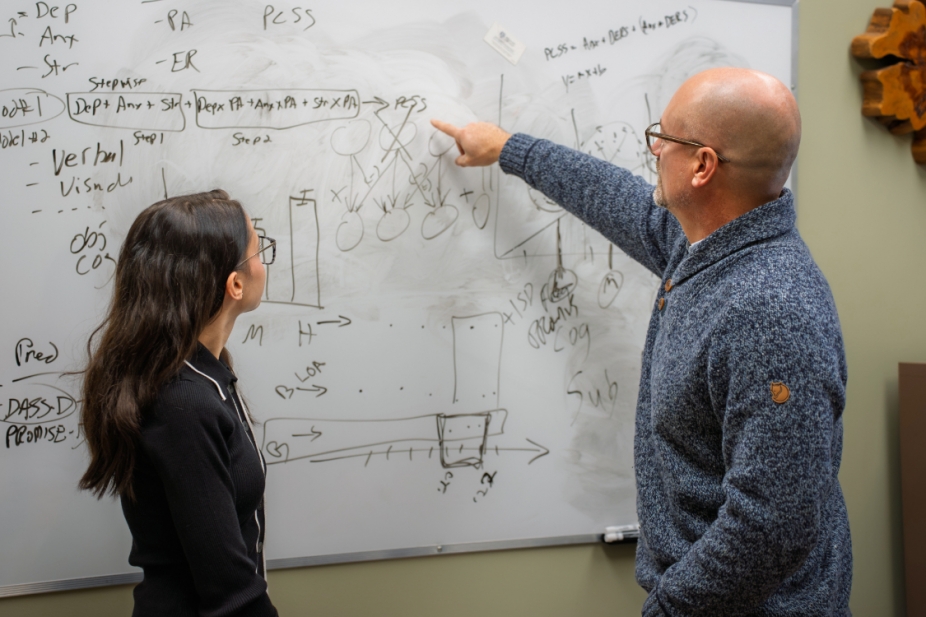

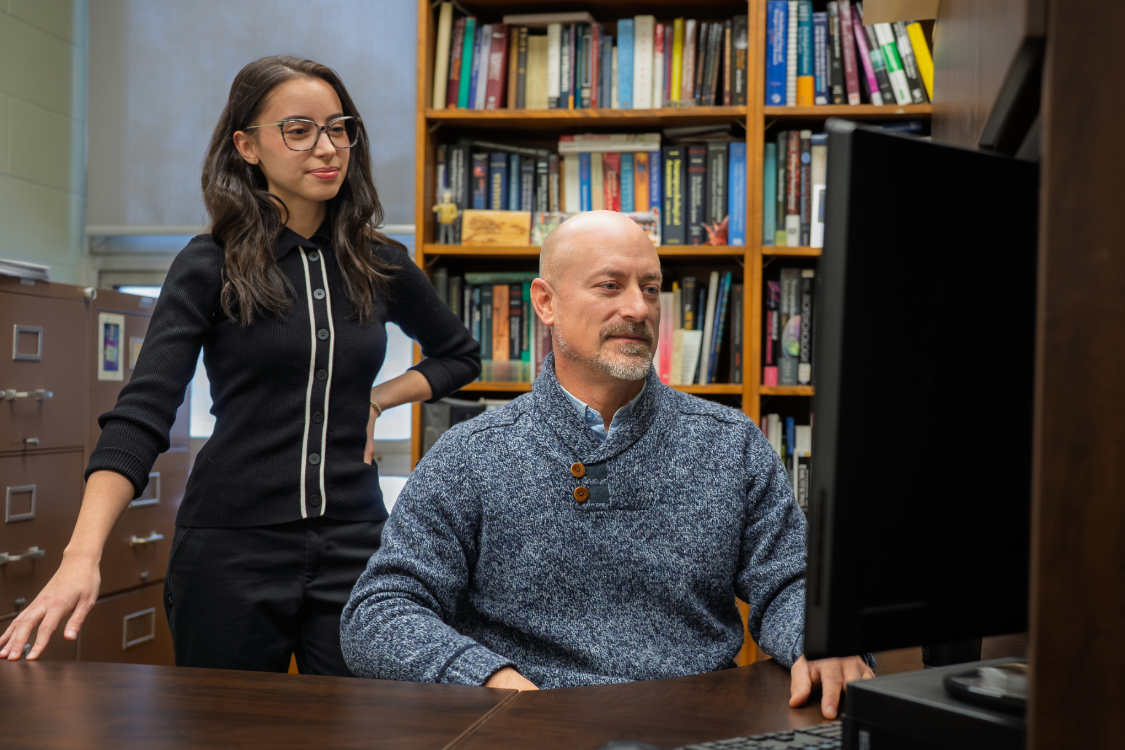

Neuropsychology PhD student Vanessa Correia and professor Dr. Christopher Abeare, who also serves as clinical supervisor at the Sport-Related Concussion Centre (SRCC)

at the University of Windsor in Windsor, Ont., on Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2025. (DAVE GAUTHIER/ University of Windsor)

We spend about a third of our lives asleep, and those hours are crucial for everything from mood to muscle repair.

Now, University of Windsor researchers are asking whether poor sleep could put athletes at greater risk of concussion—and affect how they recover.

“There’s tons of new research coming out about sleep, and it’s super important for many different things,” said neuropsychologist and professor Dr. Christopher Abeare, who also serves as clinical supervisor at the Sport-Related Concussion Centre (SRCC) on campus.

“If you have poor sleep, you’re at increased risk of diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease and heart conditions. During sleep, the brain goes through a process of cleaning and repairing itself. And after a concussion, poor sleep is quite likely to slow down recovery.”

Abeare’s lab studies how concussions and traumatic brain injuries affect thinking and emotions, collecting data that could one day improve assessment and treatment.

Assessing risk factors

Neuropsychology PhD student Vanessa Correia is examining sleep as a potential risk factor for concussion, calling it a missing piece of the puzzle.

“There is some research on risk factors, like sex, age, concussion history or migraines, that can make recovery more complicated,” she explained.

“There’s also some research about sleep post-concussion. We know it’s often disturbed — people sleep more and with worse quality — but little is known about how pre-injury sleep affects outcomes.”

That gap is what Correia hopes to fill.

She notes that students already tend to have poor sleep due to shifting routines, academic responsibilities and other pressures. Athletes, who are the clinic’s main focus, face additional challenges such as long practice days, travel and balancing sport with coursework.

“I thought it would be interesting to see how sleep before they’ve ever had a concussion — their baseline — relates to whether they get a concussion or not,” she said. “If they have poor sleep before, does that mean they have more symptoms when they do get one? Does it take them longer to bounce back?”

While the research is still in early stages, Abeare believes it has the potential to be significant.

“I suspect pre-existing sleep problems before a concussion may lead to a longer or worse recovery,” he said.

Another project in the lab examines the role of sleep after a concussion in the recovery process, contributing to the team’s wider research into the factors that influence outcomes following brain injuries.

They’re also exploring how emotional regulation affects progress post-injury.

“There are four different classes of symptoms you can have after a concussion, one of which is emotional,” said Abeare. “People can be irritable or develop anxiety or depression.

“We’re looking at whether people who have better emotion-regulation skills to begin with tend to have fewer of these problems after a concussion.”

Correia added that preventing concussions is easier than treating them, which is why identifying risk factors is essential.

“If we can determine what types of people are at higher risk, that can help us address those issues before an injury happens,” she said.

“For example, if sleep is a risk factor—and we know poor sleep is common among athletes — we want to find ways to improve that, so they’re not at greater risk for a concussion or more severe symptoms afterward.”

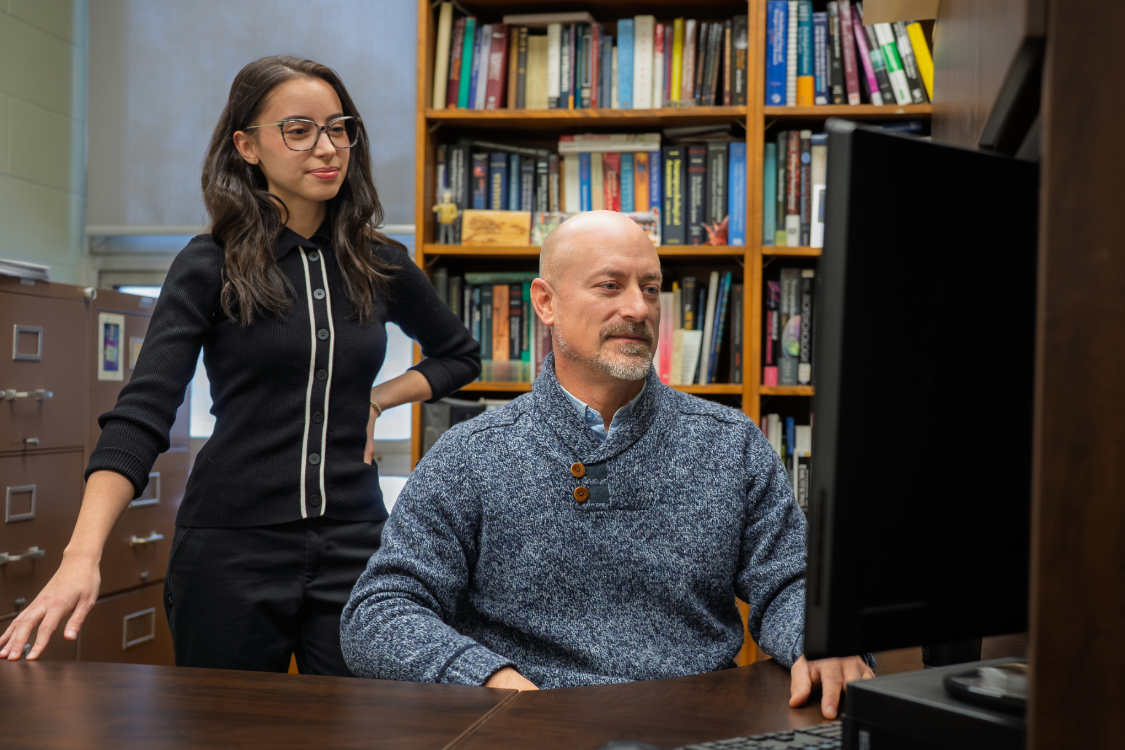

Neuropsychology PhD student Vanessa Correia and professor Dr. Christopher Abeare, who also serves as clinical supervisor at the Sport-Related Concussion Centre (SRCC)

at the University of Windsor in Windsor, Ont., on Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2025. (DAVE GAUTHIER/ University of Windsor)

Inside the brain

A concussion is a mild traumatic brain injury, most often caused by a blow to the head, though it can occur in other ways. So, what exactly happens inside the brain?

Abeare explained that the brain sits inside the skull surrounded by protective layers and cerebrospinal fluid, which helps cushion it from physical force.

“It’s a very viscous liquid, kind of like a liquid cushion. During a concussion, the brain gets rattled pretty hard, and because it’s the consistency of firm Jello, it moves. It’s not a unitary structure —there are subcomponents within it, and they all move slightly differently when force is applied,” he said.

That movement can stretch axons — the long fibres of neurons — which disrupts the flow of ions and chemicals in and out of cells, triggering a temporary state of “chaos” known as the neural metabolic cascade.

This cascade affects many brain functions, including emotional processing. Abeare explained that the release of glutamate — an excitatory neurotransmitter — can overstimulate neurons in areas tied to emotion.

“Regions involved in anxiety, fear and irritability see increased activity, while others experience decreased blood flow,” he said. “These factors combined create an energy crisis. There’s increased demand for energy and decreased ability to supply it.”

That’s one reason sleep is so vital to recovery.

“These days, we recommend that our athletes rest for two days before gradually returning to normal activities under supervision,” he said.

Neuropsychology professor Dr. Christopher Abeare, who also serves as clinical supervisor at the Sport-Related Concussion Centre (SRCC)

at the University of Windsor in Windsor, Ont., on Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2025. (DAVE GAUTHIER/ University of Windsor)

Sport-Related Concussion Centre

Before their seasons begin, Lancer athletes meet with Abeare and the SRCC clinical team for pre-season assessment — often before any injury has occurred.

“We see athletes from high-contact sports like football and hockey, but also soccer, basketball and volleyball,” Abeare said. “We run baseline testing, giving them a series of assessments — symptom checklists, cognitive tests and background surveys.”

Athletes only return to the clinic if they are suspected of having a concussion. Athletic therapists, who are on the sidelines during games and practices, flag players for follow-up.

“What’s unique about our research is that we have data on athletes before they’re injured,” Abeare said. “That’s unheard of in most clinical settings. We don’t have to guess what someone was like before—we know.”

The clinical team then compares the athlete’s post-injury performance with their baseline results.

“We put it all together to figure out what’s happening with the athlete,” he said. “At the end of the day, the main question is: do they have a concussion, and if so, are they ready to return to play?”

The clinic may also recommend steps to support recovery and reduce the risk of future injury.

In addition to serving student-athletes, the SRCC also offers rare training opportunities for neuropsychology students.

“Our PhD students are getting excellent experience with recent concussions,” said Abeare. “That’s rare in neuropsychology, where you usually see people a year or two after the fact, when symptoms persist.”

Correia, who serves as the clinical coordinator at the SRCC and is completing her practicum there, said each case brings something new.

“On the outside, it might seem like a homogenous group—mostly male football players, the athletes in high-contact sports,” she said. “But there’s actually a lot of variability in background and symptom presentation.”

“No two concussions are the same. Each case is different, and each one is a chance to learn.”

Neuropsychology PhD student Vanessa Correia and professor Dr. Christopher Abeare, who also serves as clinical supervisor at the Sport-Related Concussion Centre (SRCC) at the University of Windsor in Windsor, Ont., on Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2025. (DAVE GAUTHIER/ University of Windsor)

Athletes at the centre

Student-athletes also play a key role in the research.

“We’re lucky to partner with the concussion clinic, which gives us access to multiple sources of data,” Correia said.

“Having both baseline and post-injury data gives us a clear picture of what’s happening. Without something to compare to, it’s hard to interpret those changes.”

Abeare hopes the lab’s research will not only improve understanding of sport-related brain injuries, but also shape better treatment.

“From a clinical standpoint, I want to help people,” he said. “And athletes give us a unique window into concussion—they’re among the healthiest individuals likely to get one, and they’re highly motivated to recover and return.”

Learn more about the research and services offered through Dr. Abeare’s lab and the Sport-Related Concussion Centre at abearelab.com and uwindsor.ca/concussion.

Courtesy: Lindsay Charlton https://www.uwindsor.ca/news/2025-12-16/exploring-hidden-factors-influence-concussion-recovery-athletes